Published in "La ville rebelle. Démocratiser le projet urbain", 2015 Gallimard, ISBN : 9782072619564

Missis Chen is 84 years old. She has lived together with the Xindian River all her life. Her family used to have a boat, like every Taipei family, and a water buffalo. Sometimes the kids would cross the river on the back of the buffalo. Sometimes an uncle might end up so drunk, that they hesitated, if they could put him back on his boat after an evening together. Children, vegetables and laundry were washed in the river. The water was drinkable and the river was full of fish, crabs, snails, clams, shrimp and frogs to eat.

Missis Chen used to work for sand harvesters, who dug sand out of the river bottom for making concrete. She made food for them. Many of the sand harvesters lived in the Treasure Hill settlement together with Missis Chen’s family. In the past the hill had been a Japanese Army anti-aircraft position, and it was rumored that the Japanese had hidden a treasure of gold somewhere in their bunker networks inside the hill - hence the name Treasure Hill.

Xindian River was flooding - like all Taipei rivers - when the frequent typhoons arrived in summers and autumns. The flood was not very high, though – the Taipei Basin is a vast flood plain and water has plenty of space to spread out. Houses were designed so that the knee high flood would not come in or in some places the water was let into the ground floor, while people continued to live in the upper floors. In Treasure Hill the flood would also come into the piggeries and other light-weight structures on the river flood bank, but the houses with people were a bit higher up on the hill. All of the flood bank were farmed, and the farms and vegetable gardens were constructed so that they could live together with the flood. Flooding was normal. This pulse of nature was a source of life.

Missis Chen remembers when the river got polluted. “The pollution comes from upstream”, she says, referring to the many illegal “Made in Taiwan” -factories up on the mountains and river banks, which let all their industrial waste into the river. “Now not even the dogs eat the fish anymore.” At some point the river became so polluted that Taipei children were taught not to touch the water or they would go blind. The flood became poisonous for the emerging industrial city, which could no longer live together with the river nature. The city built a wall against the flooding river: a 12 meters high, reinforced concrete flood wall separating the built urban environment from nature.

![]() |

| Taipei flood wall |

“One day, the flood came to Chinag Kai-Shek’s home and the Dictator got angry. He built the wall. We call it the Dictator’s Wall,” An elderly Jiantai fisherman recalls sitting in his bright blue boat with a painted white eye and red mouth and continues to tell his stories describing, which fish disappeared which year, and when some of the migrating fishes ceased to return to the river. In one lifetime, the river has transformed from a treasure chest of seafood into an industrial sewer, which is once again being slowly restored towards a more natural condition. The wall hasn’t moved anywhere. The generations of Taipei citizens born after 1960’s don’t live in a river city. They live in an industrially walled urban fiction separated from nature.

TREASURE HILL

In 2003 the Taipei City Government decided to destroy the unofficial settlement of Treasure Hill. By that time, the community consisted of some 400 households of mainly elderly Kuomintang veterans and illegal migrant workers. The bulldozers had knocked down the first two layers of the houses of the terraced settlement on the hillside. After that the houses were standing too high for the bulldozers to reach, and there were no drivable roads leading into the organically built settlement. Then the official city destroyed the farms and community gardens of Treasure Hill down by the Xindian River flood banks. Then they cut the circulation between the individual houses – small bridges, steps, stairs and pathways. After that, Treasure Hill was left to rot, to die slowly, cut away from its life sources.

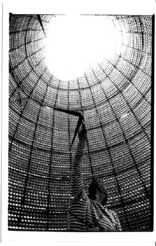

![]() |

| Treasure Hill |

Roan Chin-Yueh of the WEAK! managed the City Government Department of Cultural Affairs to invite me to Taipei and introduced Treasure Hill’s impressive organic settlement with self-made root-cleaning system of grey waters through patches of jungle on the hillside; composting of organic waste for fertilizer to the farms and using minimum amounts of electricity, which they stole from the official grid. There was even a central radio system through which Missis Chen could transmit important messages to the community, such as inviting them to watch old black and white movies in the open-air cinema in front of her house.

At that point the city had stopped to collect trash from Treasure Hill, and there were lots of garbage bags in the alleys. I started to collect these garbage bags and carried them down the hill into a pile close to a point which you could reach with a truck. The residents did not speak to me, but instead they hid inside their houses. One could feel their eyes on one’s back, though. Some houses were abandoned and I entered them. The interiors and the atmospheres were as if the owners had left all of a sudden. Even photo albums were there and tiny altars with small gods with long beards. In one of the houses I could not help looking at the photo album. The small tinted black and white photos started in Mainland China, and all the guys wore Kuomintang military uniforms. Different landscapes in different parts of China and then in some point the photos turned to color prints. The same guys were in Taiwan. Then there was a woman and an elder gentleman posed with her in civil clothes by a fountain. Photos of children and young people. Civil clothes, but the Kuomintang flag of Taiwan everywhere. A similar flag was inside the room. Behind me somebody enters the house, which is only one room with the altar on the other end and a bed on the other. The old man is looking at me. He is calm and observant, somehow sad. He speaks and shows with his hand at the altar. Do not touch – I understand. I look at the old man in the eyes and he looks into mine. I feel like looking at the photo album. The owner of the house must have been his friend. They have travelled together a long way from the civil war of China to Taiwan. They have literally built their houses on top of Japanese concrete bunkers and made their life in Treasure Hill. His friend has passed away. There is a suitcase and I pack inside the absent owner’s trousers and his shirt, both in khaki color. I continue collecting the garbage bags and carry the old man’s bag around the village. The next day the residents start helping me with collecting the garbage. Professor Kang Min-Jay organizes a truck to take the bags away. After a couple of days we organize a public ceremony together with some volunteer students and Treasure Hill veterans and declare a war on the official city: Treasure Hill will fight back and it is here to stay. I’m wearing the dead man’s clothes.

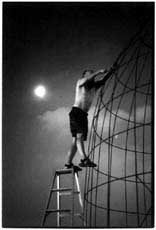

![]() |

| Collective farm in Treasure Hill |

We have a long talk with Professor Roan about Treasure Hill and how to stop the destruction. He suggests that Hsieh Ying-Chun (Atelier 3, WEAK!) will join us with his aboriginal Thao tribe crew of self-learned construction workers. I start touring in local universities giving speeches about the situation and try to recruit students for construction work. In the end we have 200 students from Tamkang University Department of Architecture, Chinese Cultural University and National Taiwan University. A team of attractive girl students manage to make a deal with the neighboring bridge construction site workers and they start offloading some of the construction material cargo from the trucks passing by to us. We mainly get timber and bamboo; they use mahogany for the concrete molds.

With the manpower and simple construction material we start reconstructing the connections between the houses of the settlement, but most importantly, we also restart the farms. The bridge construction workers even help us with a digging machine. Missis Chen comes to advise us about the farming and offers us food and Chinese medicine. I am invited to her house every evening after the work day with an interpreter. She tells her life story and I see how she is sending food to many houses whose inhabitants are very old. Children from somewhere come to share our dinners as well. Her house is the heart of the community. Treasure Hill veterans join us in the farming and construction work. Rumors start spreading in Taipei: things are cooking in Treasure Hill. More people volunteer for the work and after enough urban rumors the media arrives suddenly. After the media, the politicians follow. Commissioner Liao from the City Government Cultural Bureau comes to recite poems. Later Mayor Ma Ying-Jeou comes jogging by with TV crews and gives us his blessings. The City Government officially agrees that this is exactly why they had invited me from Finland to work with the issue of Treasure Hill. The same government had been bulldozing the settlement away 3 weeks earlier. One can design whole cities simply with rumors.

![]() |

| Reconstructed steps in Treasure Hill |

Working in Treasure Hill had pressed an acupuncture point of the industrial Taipei City. Our humble construction work was the needle which had penetrated through the thin layer of official control and touched the original ground of Taipei – collective topsoil where Local Knowledge is rooting. Treasure Hill is an urban compost, which was considered a smelly corner of the city, but after some turning is now providing the most fertile topsoil for future development. The Taiwanese would refer to this organic energy as “Chi”.

URBAN ACUPUNCTURE

After the initial discovery in Treasure Hill, the research of Urban Acupuncture continued at the Tamkang University Department of Architecture, where Chairman Chen Cheng-Chen under my professorship added it into the curriculum in the autumn of 2004. In 2009 the Finnish Aalto University’s Sustainable Global Technologies research center with Professor Olli Varis joined in to further develop the multi-disciplinary working methods of Urban Acupuncture in Taipei, with focus on urban ecological restoration through punctual interventions. In 2010, the Ruin Academy was launched in Taipei with the help of the JUT Foundation. The Academy operated as an independent multidisciplinary research center moving freely in-between the different disciplines of art and science within the general framework of built human environment. The focus was on Urban Acupuncture and the theory of the Third Generation City. Ruin Academy collaborated with the Tamkang University Department of Architecture, the National Taiwan University Department of Sociology, Aalto University SGT, the Taipei City Government Department of Urban development and the International Society of Biourbanism.

![]() |

| Un-official community gardens and urban farms of Taipei Basin, the real map of Urban Acupuncture. |

Urban Acupuncture is a biourban theory, which combines sociology and urban design with the traditional Chinese medical theory of acupuncture. As a design methodology, it is focused on tactical, small scale interventions on the urban fabric, aiming in ripple effects and transformation on the larger urban organism. Through the acupuncture points, Urban Acupuncture seeks to be in contact with the site-specific Local Knowledge. By its nature, Urban Acupuncture is pliant, organic and relieves stress and industrial tension in the urban environment - thus directing the city towards the organic: urban nature as part of nature. Urban Acupuncture produces small-scale, but ecologically and socially catalytic development on the built human environment.

Urban Acupuncture is not an academic innovation. It refers to common collective Local Knowledge practices that already exist in Taipei and other cities. Self-organized practices which are tuning the industrial city towards the organic machine, the Third Generation City.

In Taipei, the citizens ruin the centrally governed, official mechanical city with unofficial networks of urban farms and community gardens. They occupy streets for night markets and second hand markets, and activate idle urban spaces for karaoke, gambling and collective exercises (dancing, Tai-Chi, Chi-Gong etc.). They build illegal extensions to apartment buildings, and dominate the urban no man’s land by self-organized, unofficial settlements such as Treasure Hill. The official city is the source of pollution, while the self-organized activities are more humble in terms of material energy-flows and more tied with nature through the traditions of Local Knowledge. There is a natural resistance towards the official city. It is viewed as an abstract entity that seems to threaten the community sense of people and separates them from the biological circulations. Urban Acupuncture is Local Knowledge in Taipei, which in larger scale is keeping the official city alive. The un-official is the biological tissue of the mechanic city. Urban Acupuncture is a biourban healing and development process connecting the modern man with nature.

THIRD GENERATION CITY

The First generation city were the human settlements in straight connection with nature and dependent on nature. The fertile and rich Taipei Basin provided a fruitful environment for such a settlement. The rivers were full of fish and good for transportation, with the mountains protecting the farmed plains from the straightest hits of the frequent typhoons.

The second generation city is the industrial city. Industrialism granted the citizens independence from nature - a mechanical environment could provide everything humans needed. Nature was seen as something unnecessary or as something hostile - it was walled away from the mechanical reality.

The Third Generation City is the organic ruin of the industrial city, an open form, organic machine tied with Local Knowledge and self-organized community actions. The community gardens of Taipei are fragments of third generation urbanism when they exist together with the industrial surroundings. Local Knowledge is present in the city, and this is where Urban Acupuncture is rooting. Among the anarchist gardeners are the local knowledge professors of Taipei.

The Third Generation City is a city of cracks. The thin mechanical surface of the industrial city is shattered, and from these cracks emerge the new biourban growth which will ruin the second generation city. Human-industrial control is opened up in order for nature to step in. A ruin is when manmade has become part of nature. In the Third Generation City we aim in designing ruins. Third Generation City is true when the city recognizes its local knowledge and allows itself to be part of nature.

"To find a form that accommodates the mess, that is the task of the artist now."

- Samuel Beckett

![]() |

| Paracity, model |

Paracity is a biourban organism that is growing on the principles of Open Form: individual design-built actions generating spontaneous communicative reactions on the surrounding built human environment. This organic constructivist dialog leads to self-organized community structures, sustainable development and knowledge building. Open Form is close to the original Taiwanese ways of developing the self-organized and often “illegal” communities. These micro-urban settlements containe a high volume of Local Knowledge, which we believe will start composting in Paracity, once the development of the community is in the hands of the citizens.

![]()

The architectural organism of the Paracity is based on a three-dimensional, wooden primary structure, an organic grid with spatial modules of 6 x 6 x 6 meters, constructed out of CLT (cross-laminated timber) beams & columns. This simple structure can be modified and developed by the community members. The primary structure can grow even in neglected urban areas such as flood plains, hillsides, abandoned industrial areas, storm water channels and slums. Paracity is perfectly suited for flooding and tsunami risk areas and the CLT primary structure is highly fire-resistant and capable of withstanding earthquakes.

![]()

Paracity provides the skeleton, but the citizens create the flesh. Design should not replace reality, Flesh is More. Paracitizens will attach their individual, self-made architectural solutions, gardens and farms on the primary structure, which will offer a three dimensional building grid for DIY architecture. The primary structure also provides the main arteries of water and human circulation, but the finer Local Knowledge nervous networks are weaved in by the inhabitants. Large parts of Paracity is occupied by wild and cultivated nature following the example of Treasure Hill and other un-official communities in Taipei.

![]() |

| Paracity CLT-module, 6x6x6 m |

Paracity’s self-sustainable biourban growth is backed up by off-the-grid modular environmental technology solutions, providing methods for water purification, energy production, organic waste treatment, waste water purification and sludge recycling. These modular plug-in components can be adjusted according to the growth of the Paracity and moreover, the whole Paracity is designed not only to treat and circulate its own material streams, but to start leeching waste from its host city and thus becoming a positive urban parasite following the similar kinds of symbiosis as in-between slums and the surrounding city. In a sense Paracity is a high-tech slum, which can start tuning the industrial city towards an ecologically more sustainable direction. Paracity is a Third Generation City, an organic machine, urban compost, which assists the industrial city to transform into being part of nature.

The pilot project of the Paracity grows on an urban farming island of Danshui River, Taipei City. The island is located between the Zhongxing and Zhonxiao bridges and is around 1000 meters long and 300 meters wide. Paracity Taipei celebrates the original first generation Taipei urbanism with a high level of “illegal” architecture, self-organized communities, urban farms, community gardens, urban nomads and constructive anarchy.

![]()

After the Paracity has reached critical mass, the life providing system of the CLT structure will start escalating. It will cross the river and start taking root on the flood plains. It will then cross the 12 meter high Taipei flood wall and gradually grow into the city. The flood wall will remain in the guts of the Paracity, but the new structure enables Taipei citizens to fluently reach the river. Paracity will reunite the river reality and the industrial urban fiction. Paracity is a mediator between the modern city and nature. Seeds of the Paracity will start taking root within the urban acupuncture points of Taipei: illegal community gardens, urban farms, abandoned cemeteries and wastelands. From these acupuncture points, Paracity will start growing by following the covered irrigation systems such as the Liukong Channel, and eventually the biourban organism and the static city will find a balance, the Third Generation Taipei.

Paracity has a lot of holes, gaps and nature in between houses. The system ventilates itself like a large scale beehive of post-industrial insects. The different temperatures of the roofs, gardens, bodies of water and shaded platforms will generate small winds between them, and the hot roofs will start sucking in breeze from the cooler river. The individual houses should also follow the traditional principles of bioclimatic architecture and not rely on mechanical air-conditioning.

The biourbanism of the Paracity is as much landscape as it is architecture. The totalitarian landscape-architecture of Paracity includes organic layers for natural water purification and treatment, community gardening, farming and biomass production as an energy source. Infrastructure and irrigation water originates from the polluted Danshui River and will be both chemically (bacteria based) and biologically purified before being used in the farms, gardens and the houses of the community. The bacteria/chemically purified water gets pumped up to the roof parks on the top level of the Paracity, from where it will by gravity start circulating into the three dimensional irrigation systems.

![]() |

| Paracity, flood-water scenario |

Paracity is based on free flooding. The whole city stands on stilts, allowing the river to pulsate freely with the frequent typhoons and storm waters. The Paracity is actually an organic architectural flood itself, ready to cross the flood wall of Taipei and spread into the mechanical city.

Paracity Taipei will be powered mostly by bioenergy that uses the organic waste, including sludge, taken from the surrounding industrial city and by farming fast growing biomass on the flood banks of the Taipei river system. Paracity Taipei will construct itself through impacts of collective consciousness, and it is estimated to have 15.000 – 25.000 inhabitants.

The wooden primary structure and the environmental technology solutions will remain pretty much the same no matter in which culture the Paracity starts to grow, but the real human layer of self-made architecture and farming will follow the Local Knowledge of the respective culture and site. Paracity is always site-specific and it is always local. Other Paracities are emerging in North Fukushima in Japan and the Baluchistan Coast in Pakistan.

CONCLUSION

The way towards the Third Generation City is a process of becoming a collective learning and healing organism and to reconnect the urbanized collective consciousness with nature. In Taipei, the wall between the city and the river must go. This requires a total transformation from the city infrastructure and from the centralized power control. Otherwise, the real development will be unofficial. Citizens on their behalf are ready and are already breaking the industrial city apart by themselves. Local knowledge is operating independently from the official city and is providing punctual third generation surroundings within the industrial city: Urban Acupuncture for the stiff official mechanism.

The weak signals of the unofficial collective consciousness should be recognized as the futures’ emerging issues; futures that are already present in Taipei. The official city should learn how to enjoy acupuncture, how to give up industrial control in order to let nature step in.

The local knowledge based transformation layer of Taipei is happening from inside the city, and it is happening through self-organized punctual interventions. These interventions are driven by small scale businesses and alternative economies benefiting from the fertile land of the Taipei Basin and of leeching the material and energy streams of the official city. This acupuncture makes the city weaker, softer and readier for a larger change.

The city is a manifest of human-centered systems – economical, industrial, philosophical, political and religious power structures. Biourbanism is an animist system regulated by nature. Human nature as part of nature, also in the urban conditions. The era of pollution is the era of industrial urbanism. The next era has always been within the industrial city. The first generation city never died. The seeds of the Third Generation City are present. Architecture is not an art of human control, it is an art of reality. There is no other reality than nature.

Marco Casagrande

La ville rebelleOuvrage collectif de Christopher Alexander, Al Borde, Marco Casagrande, Santiago Cirugeda, Marie-Hélène Contal, Salma Samar Damluji, Yona Friedman, Lu Wenyu,Philippe Madec, Juan Román, Rotor et de Wang Shu. Édition publiée sous la direction de Jana Revedin

Textes traduits de l'anglais par Édith Ochs et de l'espagnol par Varinia Taboada et Francisca Burgos

Collection Manifestô - Alternatives, Gallimard

References:

Adorno, T. & Horkheimer, M. (1944). Dialectic of Enlightenment.New York: Stanford University Press.

Casagrande Laboratory. (2010). Anarchist Gardener. Taipei: Ruin Academy.

Web: http://issuu.com/ruin-academy/docs/anarchist_gardener_issue_one

Casagrande Laboratory CURE. (2014). Paracity. Helsinki: Habitare.

Web: http://issuu.com/clab-cure/docs/paracity_helsinki_issuu

Casagrande, M. (2008) Cross-over Architecture and the Third Generation City. Epifanio, vol.9. Tallinn: AS Printon Trükikoda.

Web: http://www.epifanio.eu/nr9/eng/cross-over.html

Casagrande, M. (2009). Guandu: River Urbanism. Taiwan Architect Magazine. Taiwan.

Web: http://casagrandetext.blogspot.com/2009/10/guandu-river-urbanism.html

Casagrande, M. (2010). Taipei Orbanic Acupuncture. P2P Foundation.

Web: http://blog.p2pfoundation.net/the-community-gardens-of-taipei/2010/12/04

Casagrande, M. (2011) Taipei from the River. Rome: International Society of Biourbanism.

Web: http://www.biourbanism.org/taipei-from-the-river/

Casagrande, M. (2011). Ruin Academy. Epifanio, vol.14. Tallinn: AS Printon Trükikoda.

Web: http://www.epifanio.eu/nr14/eng/ruin_academy.html

Casagrande, M. (2011). Illegal Architecture. Canada: Egodesign.

Web: http://www.egodesign.ca/fr/actualite_details.php?actualite_id=1746

12

Casagrande, M. (2011). Urban Ecopuncture. La Vie, vol.90. Taiwan.

Web: http://casagrandetext.blogspot.com/2011/10/urban-ecopuncture.html

Casagrande, M. (2013). Biourban Acupuncture – From Treasure Hill of Taipei to Artena. Rome: International Society of Biourbanism.

Campbell-Dollagham, K.Illegal Architecture in Taipei. Architizer.

Web: http://www.architizer.com/en_us/blog/dyn/18012/peoples-architecture-in-taipei/

Harrison, A. (2012). Architectural Theories of the Environment: Post Human Territory. New York: Routledge.

Coulson, N. (2011). Returning Humans to Nature and Reality. Taipei: eRenlai.

Web: http://www.erenlai.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=4520%3Areturning-man-to-nature-and-reality&catid=697%3Amay-focus&Itemid=348&lang=en

Harbermas, J. (1985). The Theory of Communicative Action. Boston: Beacon Press.

Inayatullah, S. (2002). Questioning the future: Methods and Tools for Organizational and Societal Transformation. Taipei: Tamkang University Press.

Kajamaa V., Kangur K., Koponen R., Saramäki N., Sedlerova K., Söderlind S. (2012). Sustainable Synergies – The Leo Kong Canal. Aalto University Sustainable Global Technologies.

Web: http://thirdgenerationcity.pbworks.com/w/file/53734479/Aalto%20University_SGT_Taipei_Final_report_15.5.2012.pdf

Kang, M. (2005). Confronting the Edge of Modern Urbanity – GAPP (Global Artivists Participation Project) at Treasure Hill, Taipei. Asian Modernity and the Role of Culture Cities, Asian Culture Symposium, Gwangju, Korea.

Web: http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&ved=0CCAQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fcct.go.kr%2Fdata%2Facf2005%2FS2_3(Asia%2520culture%2520Symposium2).doc&ei=Py6GUJKcM8Ti4QTL24HAAg&usg=AFQjCNEA--xWIUBQGFkDdmetSUIv-fd-uQ&sig2=TfNut-1SFBNvKobfgwJlYA

Kaye, L. (2010). Could cities' problems be solved by urban acupuncture? London: The Guardian.

Web: http://www.guardian.co.uk/sustainable-business/urban-acupuncture-community-localised-renewal-projects

Lang, F. (1927). Metropolis. Germany: UFA.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1955). Tristes Tropiques. New York: Atheneum.

Pajunen, M. A Man from the Woods. Wastelands Magazine. Finland.

Web: http://casagrandetext.blogspot.fi/2012/08/a-man-in-woods.html

Richardson, P. (2011). From the Ruins, Taipei to Detroit. Archetcetera.

Web: http://archetcetera.blogspot.com/2011/01/from-ruins-taipei-to-detroit.html

14

Shen, S. (2014). AW Architectural Worlds, vol. 156. Shenzhen: Haijian Printing Co.

Web: http://issuu.com/clab-cure/docs/casagrande_laboratory___architectua/1?e=11086647%2F10750378

Stevens, P. (2014). interview with marco casagrande, principal of C-LAB. Designboom.

Web: http://www.designboom.com/architecture/marco-casagrande-laboratory-interview-10-14-2014/

Strugatsky, A., Strugatsky B. (1971). Roadside Picnic. London: McMillan.

Tarkovsky, A. (1979). Stalker. Moscow: Mosfilm.

White, R. (1995). The Organic Machine: The Remaking of the Columbia River. New York: Hill and Wang.

Yudina, A. it’s anarchical it’s acupunctural, well it’s both / marco casagrande. Monitor Magazine, vol,68. Berlin.

Web: http://casagrandetext.blogspot.fi/2012/09/its-anarchical-its-acupunctural-well.html

.jpg)